“The purely economic man is indeed close to being a social moron. Economic theory has been much preoccupied with this rational fool.”

— Richard H. Thaler

Introduction

As Nobel laureate Thaler contends, the economic science has been far too preoccupied with the purely economic man. This insight has never been more relevant. In a world defined by populist upheaval, with Brexit as its most striking British manifestation, the limitations of traditional economic models have been laid bare.

Despite a near-unanimous consensus among economists on the damaging consequences of leaving the EU, 52% of the British electorate nevertheless voted to do so [1]. This outcome, seemingly irrational and self-sacrificing when judged by material interests, highlights the failure of models that reduce human motivation to pecuniary incentives alone.

Whilst behavioural economics has refined these models by recognising the influence of cognitive limits and social preferences, they remain constrained in their explanatory power. This article argues that incorporating social identity into economic analysis is necessary for understanding contemporary policy changes as it offers a richer, more nuanced framework for explaining the behaviour of voters and political actors, and thus policy outcomes. It will first outline the limits of traditional and behavioural models, then examine identity-based approaches, before applying these insights to Brexit.

The Limitations of Traditional Economic Models

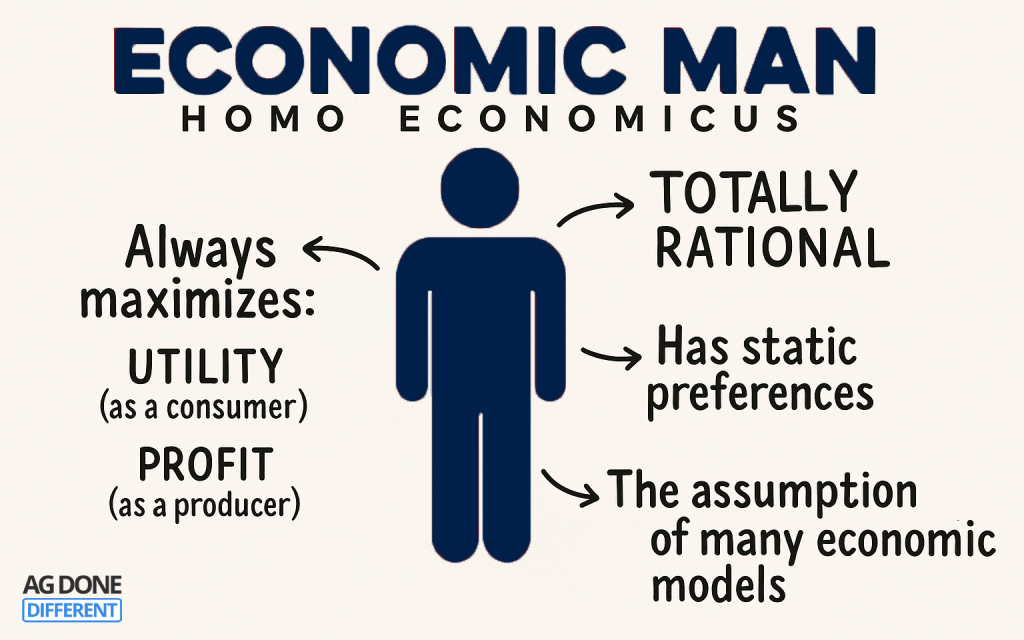

Traditional economic analysis, epitomised by rational choice theory [2] and public choice theory [3], models human behaviour on the premise of Homo economicus; a hyper-rational, self-interested agent whose preferences are stable, exogenously given, and primarily pecuniary. Rational choice theory assumes individuals make decisions by weighing costs and benefits. Public choice theory extends this logic by applying methodological individualism to political actors, treating voters, politicians, and bureaucrats as individually self-interested rational agents. This results in the modelling of political outcomes as the aggregate of individual decisions.

Despite providing powerful insights into market allocation and policy formation, these models rest on increasingly untenable assumptions. First, they overlook computational limits: bounded rationality, heuristics, and cognitive biases which prevent optimal processing of information and thus decision-making [4][5][6]. Second, they downplay non-pecuniary motivations such as inequality aversion, fairness, and reciprocity [7][8][9]. Third, they neglect social and collective dynamics which demonstrate that preferences are neither fixed nor exogenous; they are shaped endogenously by norms, group membership, and identity salience [10].

Whilst behavioural economics has made substantial progress in addressing some of these key shortcomings, economists still struggle to fully explain much self-sacrificing behaviour. For example, growing support for populist movements cannot be fully captured by social preferences and cognitive limits. Social identity provides the missing causal link necessary to comprehend this behaviour.

Identity-Based Approaches

Bénabou and Tirole [11] distinguish between personal identity: beliefs about one’s character, values, and abilities and group identity: beliefs about belonging to a collective such as a family, firm, culture, or nation. In this essay, I use social identity to refer specifically to group identity: an individual’s self-perception of belonging to a social category, whether ascribed or voluntary, and the utility derived from aligning with its norms and values [10][12].

Individuals gain utility from social conformity through alignment with group norms, internalised values, and expectations, as well as through social approval and reputation. Even when conformity entails a material cost, adhering to norms produces psychological satisfaction by reinforcing one’s self-concept and group membership [10]. This is formalised in the Akerlof-Kranton utility function:

Uj=Uj(aj,a−j,Ij)

| Where: | |

| Uj: The utility of person j | aj: The actions of person j |

| a−j: The actions of all others besides person j | Ij: Person j’s identity or self-image |

Through this lens, political decisions are not merely defined by utility gained from material consequences, but how a policy reinforces or threatens one’s sense of identity.

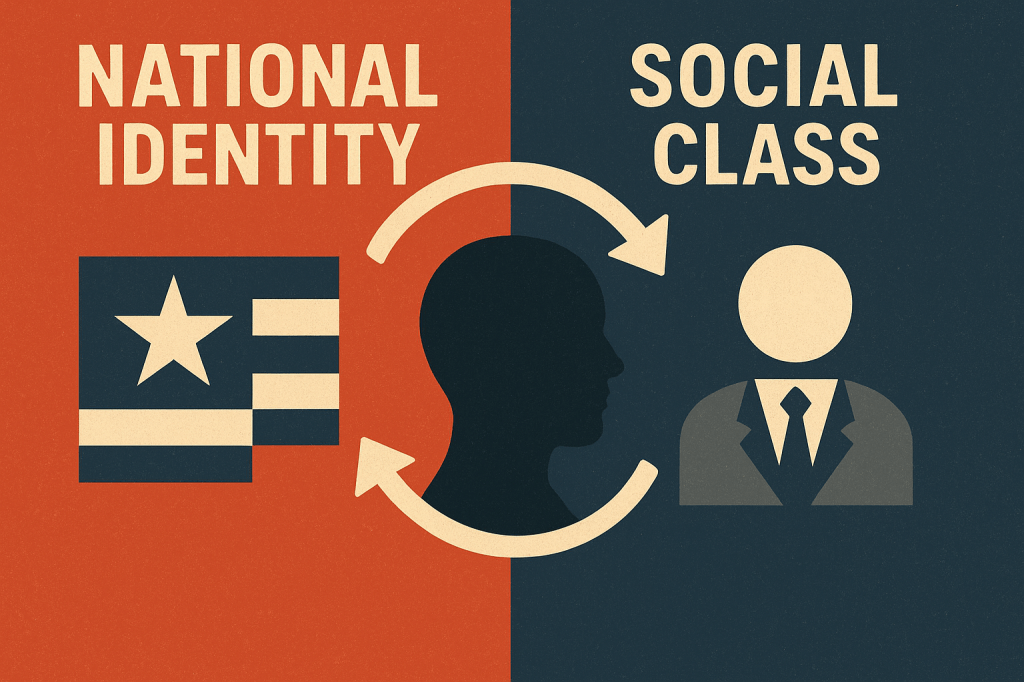

Building on this foundation, Shayo’s [13] model provides crucial insights into which identity becomes salient at any given time. Individuals will identify with the group that maximises their utility based on two key factors: group status and group homogeneity. This creates a dynamic where people shift between competing identities based on changing circumstances. The most politically relevant application concerns the tension between class and national identities. When economic shocks reduce the perceived status of one’s socioeconomic class, individuals may compensate by strengthening their identification with the nation. This shift is particularly pronounced when within-group heterogeneity increases (such as through migration) and when there are exogenous sources of national prestige.

This individual-level identity switching creates powerful political dynamics. As economically marginalised communities increasingly identify with national rather than class identity, they become more receptive to nationalist political appeals. Rational political parties, including cosmopolitan parties, recognising this shift, adjust their platforms to capture these voters. Often this is done by adopting more nationalist positions even at the expense of redistributive policies that might materially benefit their constituents. This creates what Shayo [13] terms a “Social Identity Equilibrium”; a self-reinforcing cycle, where utility from class identity diminishes given economically self-sacrificing policies and thus reinforces national identification.

Once this cycle begins, it generates lasting structural changes in the political system. We observe the emergence of authentically nationalist candidates who credibly represent these sentiments, the rise of new nationalist parties, and often the capture or transformation of existing mainstream parties [14]. Through a process of political hysteresis, these changes become institutionally embedded, making reversal extremely difficult even when economic conditions improve.

This framework explains why seemingly “irrational” political outcomes, where voters support policies that appear to harm their material interests, are quite rational when viewed through the lens of identity utility and how political hysteresis can lead to future political outcomes being economically damaging.

Counter Arguments

Whilst models of social identity can help us understand seemingly self-sacrificing policy outcomes, it faces significant criticism as it is difficult to quantify the utility derived from group memberships, and social conformity. The abstract nature of identity makes empirical validation tenuous. It risks post-hoc rationalisation, creating a circular logic where an identity-based explanation can be crafted for almost any political outcome after the fact. As Hogg and Abrams [15] note, translating complex sociological and psychological constructs into economic variables is a major challenge. This is reinforced by the risk of oversimplifying the intersectionality of complex competing and reinforcing identities [16].

Moreover, whilst models can elegantly explain why an identity shift occurred after an economic shock, they are far less effective at predicting which shock will trigger a shift and which identity will become dominant. This makes the framework a better historical tool than a proactive policy instrument.

However, I would note researchers are making progress by using survey data, laboratory experiments, and neuroeconomic tools to approximate and test these abstract concepts [13][17][18][19]. Further, perfect predictability is not a requirement for a useful economic model. Many established models, such as those for business cycles or asset prices like the Capital Asset Pricing Model, also have limited predictive power [21][22].

The value of identity economics lies in its explanatory power. It provides a crucial causal link that was previously missing, which is a necessary first step for building more robust predictive models in the future.

Case Study: Brexit & The Triumph of National Identity

The UK’s 2016 referendum illustrates the explanatory power of identity economics. Despite an overwhelming consensus among economists predicting GDP losses of 5.4 to 9.5% over 15 years (according to World Trade Organization rules) if Britain left the EU [23], 52% of voters chose Leave. Under traditional models this appears irrational. However, through the lens of social identity, it becomes comprehensible.

Survey and econometric evidence show identity, not pocketbook interests, drove the outcome. Goodwin and Heath [24] find that local areas with older, less-educated, predominantly white British populations and stronger attachment to “English” rather than “British” identity were far more likely to support Leave. Clarke, Goodwin and Whiteley [25], using British Election Study data, show immigration attitudes and national identity consistently outweighed personal economic evaluations.

Economic shocks provided fertile ground for this identity shift. Colantone and Stanig [26] show areas most exposed to Chinese import competition became UKIP strongholds before 2016 and later voted heavily Leave. Fetzer [27] demonstrates that austerity-driven welfare cuts also significantly increased Leave support. In Shayo’s [13] framework, declining class status reduces the utility of class identification, encouraging a switch to national identity as the more rewarding reference group.

The Leave campaign effectively mobilised this sentiment. Its slogan, “Take Back Control,” centred on sovereignty and cultural threat rather than economic argument. Media analyses confirm that immigration and sovereignty dominated referendum coverage, particularly in pro-Leave outlets [28].

British Election Study data show “Leaver” and “Remainer” have remained stable predictors of policy preferences long after the referendum, cutting across traditional party lines [29]. This persistence reflects Shayo’s [13] notion of identity equilibria and Besley and Persson’s [14] concept of political hysteresis, showing how once social and political identities are established and become entrenched in the political system, they become self-reinforcing and difficult to reverse even when economic conditions change.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our analysis has demonstrated that incorporating social identity into economic analysis is not merely a useful tool but a necessary one for a comprehensive understanding of contemporary policy changes. By moving beyond the traditional models, we can better explain seemingly irrational political outcomes, such as the Brexit vote, or the global rise of populism. These cases reveal how voters derive significant non-pecuniary utility from affirming their group identity, often outweighing considerations of material self-interest.

Whilst critics rightly point to the challenges of quantifying these abstract concepts, the explanatory power of identity economics provides a crucial causal link that traditional models simply lack. Therefore, to truly grasp the complex political landscape of our time, economists and policymakers must move beyond a purely pecuniary view of human behaviour and recognise the profound influence of social identity on our most important collective decisions.

References

[1] Chadha, J., Corrado, L., Meaning, J. and Schultz, T. (2016) ‘Supply side effects of monetary policy: Beyond the portfolio channel’, Working Paper No. 517. Cambridge: National Institute of Economic and Social Research.

[2] Becker, G. S. (1976) The Economic Approach to Human Behavior. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[3] Buchanan, J. M. and Tullock, G. (1962) The Calculus of Consent: Logical Foundations of Constitutional Democracy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

[4] Simon, H. A. (1972) ‘Theories of bounded rationality’, Decision and Organization, 1(1), pp. 161–176.

[5] Tversky, A. and Kahneman, D. (1974) ‘Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases’, Science, 185(4157), pp. 1124–1131.

[6] Tversky, A. and Kahneman, D. (1979) ‘Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk’, Econometrica, 47(2), pp. 263–291.

[7] Fehr, E. and Schmidt, K. M. (1999) ‘A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(3), pp. 817–868.

[8] Falk, A. and Fischbacher, U. (2006) ‘A theory of reciprocity’, Games and Economic Behavior, 54(2), pp. 293–315.

[9] Henrich, J., Boyd, R., Bowles, S., Camerer, C., Fehr, E., Gintis, H. and McElreath, R. (2001) ‘In search of homo economicus: Behavioral experiments in 15 small-scale societies’, American Economic Review, 91(2), pp. 73–78.

[10] Akerlof, G. A. and Kranton, R. E. (2000) ‘Economics and identity’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(3), pp. 715–753.

[11] Bénabou, R. and Tirole, J. (2011) ‘Identity, morals, and taboos: Beliefs as assets’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(2), pp. 805–855.

[12] Tajfel, H. and Turner, J. C. (1979) ‘An integrative theory of intergroup conflict’, in Austin, W. G. and Worchel, S. (eds.) The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Monterey: Brooks/Cole, pp. 33–47.

[13] Shayo, M. (2009) ‘A model of social identity with an application to political economy: Nation, class, and redistribution’, American Political Science Review, 103(2), pp. 147–174.

[14] Besley, T. and Persson, T. (2021) ‘Democratic values and institutions’, American Economic Review: Insights, 3(1), pp. 31–48.

[15] Hogg, M. A. and Abrams, D. (1988) Social Identifications: A Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations and Group Processes. London: Routledge.

[16] Crenshaw, K. (1989) ‘Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics’, University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), pp. 139–167.

[17] Chen, Y. and Li, S. X. (2009) ‘Group identity and social preferences’, American Economic Review, 99(1), pp. 431–457.

[18] Berns, G. S., Capra, C. M., Moore, S. and Noussair, C. (2010) ‘Neural mechanisms of the influence of popularity on adolescent ratings of music’, NeuroImage, 49(3), pp. 2687–2696.

[19] Hackel, L. M., Zaki, J. and Van Bavel, J. J. (2017) ‘Social identity shapes social valuation: Evidence from prosocial behavior and vicarious reward’, Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 12(8), pp. 1219–1228.

[20] Fama, E. F. and French, K. R. (1992) ‘The cross‐section of expected stock returns’, The Journal of Finance, 47(2), pp. 427–465.

[21] Stock, J. H. and Watson, M. W. (2004) ‘Combination forecasts of output growth in a seven‐country data set’, Journal of Forecasting, 23(6), pp. 405–431.

[22] HM Treasury (2016) The Long-term Economic Impact of EU Membership and the Alternatives. London: HM Treasury.

[23] Goodwin, M. and Heath, O. (2016) ‘The 2016 referendum, Brexit and the left behind: An aggregate‐level analysis of the result’, The Political Quarterly, 87(3), pp. 323–332.

[24] Clarke, H., Goodwin, M. and Whiteley, P. (2017) Brexit: Why Britain Voted to Leave the European Union. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[25] Colantone, I. and Stanig, P. (2018) ‘Global competition and Brexit’, American Political Science Review, 112(2), pp. 201–218.

[26] Fetzer, T. (2019) ‘Did austerity cause Brexit?’, American Economic Review, 109(11), pp. 3849–3886.

[27] Moore, M. and Ramsay, G. (2017) ‘UK media coverage of the 2016 EU Referendum campaign’, Report. London: King’s College London.

[28] Curtice, J. (2017) ‘Brexit: Behind the referendum’, Political Insight, 8(2), pp. 4–7.

[Initial Quotation] Thaler, R. H. (2015) Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, p. 11.

Leave a comment