The views expressed in this article are solely my own and do not represent the official position of YEI, a nonpartisan think tank that provides a platform for its researchers to share independent perspectives.

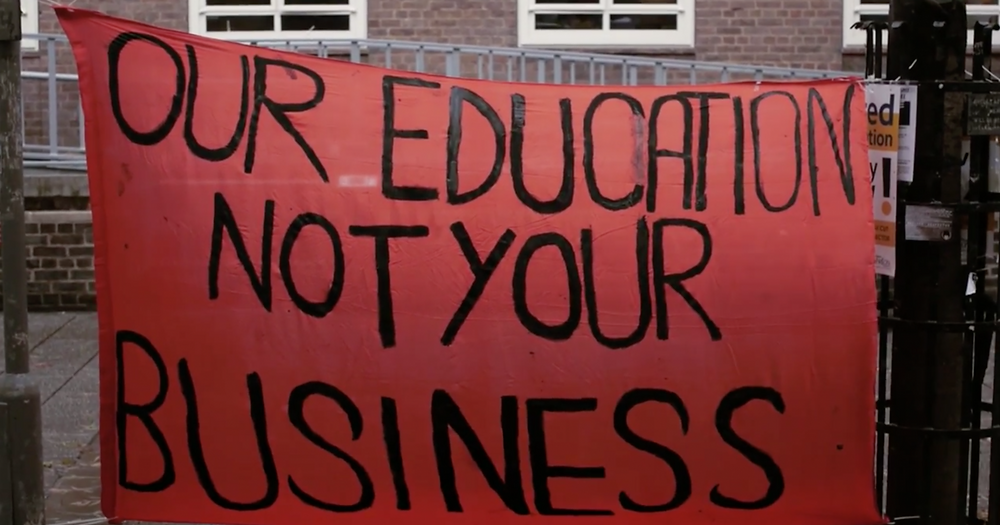

In Australia, current debates around the upcoming 2026 consolidation of two South Australian universities and the shift toward digital-first delivery are often framed as modernisation, or simply “keeping up with the times”. However, they are also symptoms of a deeper transformation. Over four decades, universities have been re-engineered to speak the language of the market: students as investments, disciplines as revenue centres, research as an asset class.

Neoliberalism is not only a set of policies; following Wendy Brown, it is a governing reason that recodes individuals as human capital and public institutions as firms, subordinating democratic and civic purposes to competitive metrics. This is how a university comes to measure its worth by graduate salaries, industry income, and rankings rather than by the knowledge and public capacities it sustains.

From public mission to market metrics

A university is a society’s research-and-conscience department: it discovers, remembers, and argues so the rest can act wisely. The classic university’s claim to serve society rested on academic freedom (scholars’ independence) and institutional autonomy (self-governance of universities) [12]. These principles are not ornaments but conditions for intellectual advancement, cultural enrichment, and democratic life.

After 1945, peaking in the 1960s, public higher education in North America experienced a “golden age”: rising literacy, expansion of the liberal arts, widened access for working-class and historically marginalised groups, and a surge in student radicalism on anti-war and civil-rights fronts. This period illustrates how freedom and autonomy correlate with thickening democratic capacities. Its decline in the 1970s marks the rise of another organising logic: neoliberal rationality, with its ROI metrics and competitive market language.

What was a public good becomes a private asset; what was education becomes human-capital accumulation. At the individual level, the question becomes: which degree maximises my earnings relative to tuition and foregone income? At the institutional level, the question becomes: which programmes, pedagogies and partnerships optimise revenue and rankings? [10]. These questions are not illegitimate. But when they become governing questions, they displace the older ones: what knowledge is valuable for a democratic society, which fields sustain cultural memory, which research anticipates slow-burn risks.

This shift is visible in funding priorities. Substantial public and private investment flows to disciplines deemed most beneficial to “the economy”, often STEM-aligned fields, while humanities and other low-profit areas are pressured to prove “market relevance”. This is accompanied by the commodification of education: rising access costs rationalised by amenities, campus expansion, and proliferating specialised degrees. Public universities begin to operate as private institutions with modest public top-ups. A familiar consequence for research is that funding tends to follow profitability rather than public urgency, e.g., in 2016, insomnia and anxiety drugs attracted outsized private capital while Ebola and HIV/AIDS vaccine research (far more urgent on public-health grounds at the time) languished for want of funding [9].

Adelaide as a case within the global pattern

South Australia has legislated the creation of a single Adelaide University, set to launch in 2026, by merging the University of Adelaide (UoA) and UniSA. The new Adelaide University has been explicitly pitched as a globally competitive institution with “top-100” ambitions and a new brand launched ahead of opening.

1. Teaching model and pedagogy

The new university has promoted a shift away from the traditional lecture toward “rich digital learning activities”, with tutorials, studios and clinics remaining face-to-face [7]. Independent reporting characterises this as ending most face-to-face lectures from 2026. Whether one reads this as innovation or cost-minimising scale, the vocabulary is unmistakably managerial and legible to rankings and throughput metrics.

2. Tuition and pricing signals

International tuition commonly sits around the A$50,000 mark for many programmes; for example Bachelor of Laws (Honours) is listed at A$54,900 for 2026 [3]. Contrast this with domestic students, where places are typically Commonwealth Supported (CSP): the state subsidises a large share and students pay a regulated student contribution (for Law, the 2026 band lists A$17,399 per EFTSL as the student contribution [4]. The two figures (separate from the Student Services & Amenities Fee) do not describe identical things but juxtaposing them makes the price architecture visible: full-fee international pricing vs subsidised domestic study. Separately, the Labor government has enacted a one-off 20% reduction to outstanding HELP balances as at 1 June 2025, with repayment settings also adjusted; important relief for domestic students, but not a structural change to headline fees [5].

3. Scholarships as price discrimination

In 2025, UoA’s Global Citizens International Scholarship offered 15% tuition reductions for 85 and above ATAR (or comparable) and 30% for a 95 and above ATAR – discounted pricing calibrated to academic rank and market competitiveness [12]. Under the merged institution, the standard automatic international award for the latter is the Adelaide Emerging Leaders Award (25%); a lower headline remission than the prior 30% tier on broadly similar academic grounds (distinction-level achievement) [2]. While there may be fiscal or administrative reasons, lowering the automatic remission from 30% to 25% with similar eligibility nonetheless functions as a margin-protecting recalibration.

For the very top of the market, UoA has also offered a 50% Global Academic Excellence scholarship; Adelaide University retains an elite 50% Academic Excellence award with limited places and criteria including a high-distinction average or a near-perfect ATAR of 99 [1][11]. Even at that altitude, an international LLB (Hons) listed at A$54,900 becomes A$27,450 per year, which is roughly A$110,000 across a four-year degree before rent, utilities and food. In ROI terms, the bottom-of-the-hierarchy actor (the student) “earns” a 50% concession for giving everything that they have, while the institution aggregates six-figure revenues not just from this one candidate but from entire cohorts. To view it simply, value created by gruelling academic labour and tremendous sacrifice is partially returned as a discount, while the surplus is appropriated by the firm-like university. What appears as opportunity is in fact yield optimistion: academic excellence harnessed for institutional gain.

Taken together, these tiers illustrate how price discrimination and merit gating operate in a marketised system: deeper remissions to attract prestige-boosting students; thinner, automatic discounts as a volume strategy; and a large middle left to pay list price.

None of this “condemns” Adelaide; it clarifies the incentive structure within which rational administrators act. When public baselines are thin and international fee revenue is structurally salient, the institution will be pushed toward scale, digital delivery, reputational metrics, and finely tuned pricing, each and all plainly visible in the Adelaide transition.

What is lost when ROI governs

First, freedom and autonomy thin out. Scholars rationally avoid controversial or long-horizon work if funding is short-term and donor-driven. The intellectual ecology narrows, precisely when it should resist narrowing.

Second, diversity contracts. A spreadsheet cannot capture the worth a language programme that prevents cultural erasure or a philosopher whose decade of work has no immediate buyer, yet neoliberal logics starve them. These fields nurture literacy, critical memory, democratic wisdom, and eventual scientific and social breakthroughs, as they always have.

Third, access as a public promise degrades. When fees and living costs rise faster than incomes, access stratifies along wealth and geography. International students from the ‘Global South’ (often positioned as “cash-cows”) bear the heaviest burden, financing not only their degrees but the survival of universities themselves. Stratification reproduces privilege rather than dismantling it.

Re-centring the public purpose

This is not to deny that employability, responsiveness, or partnerships matter. It is about proportions. A university dominated by ROI will reliably produce the kinds of knowledge that pay. But a university anchored in freedom and autonomy produces the kinds of knowledge that save: slow, critical, often unprofitable, but indispensable to democratic life.

Academic freedom and institutional autonomy are not luxuries to be bartered for efficiency. They are the foundations on which the university fulfils its mandate to deepen human understanding, advance equality, and sustain democratic life.

If the university is to serve the interests of society rather than the market alone, it must be governed by the principles that make that service possible. If not, then the university is reduced to a scam: a promise of being a hub of societal progress, discarded in the reality of being a money-making goldmine.

Adelaide’s transition makes the stakes unmistakably clear. A society that treats its universities as factories should not be surprised when they cease producing citizens.

___________________________________

Reference List

- Adelaide University n.d., Adelaide Academic Excellence Scholarship (50%), Adelaide University, viewed 14 August 2025, https://adelaideuni.edu.au/study/scholarships/int/adelaide-academic-excellence-scholarship-50/.

- Adelaide University n.d., Adelaide Emerging Leaders Award (25%), Adelaide University, viewed 14 August 2025, https://adelaideuni.edu.au/study/scholarships/int/adelaide-emerging-leaders-award-25/.

- Adelaide University n.d., Bachelor of Laws (Honours), Adelaide University, viewed 14 August 2025, https://adelaideuni.edu.au/study/degrees/bachelor-of-laws-honours/.

- Adelaide University n.d., Commonwealth Supported Students, Adelaide University, viewed 14 August 2025, https://adelaideuni.edu.au/study/how-to-apply/entry-requirements/commonwealth-supported-students/.

- Australian Government Department of Education n.d., 20% reduction of student loan debt, Australian Government Department of Education, viewed 14 August 2025, https://www.education.gov.au/higher-education-loan-program/20-reduction-student-loan-debt?.

- Brown, W 2015, Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution, Zone Books, Brooklyn.

- Cys, J & Falkner, K 2024, Creating a flexible, contemporary curriculum for Adelaide University, The University of Adelaide, viewed 14 August 2025, https://www.adelaide.edu.au/staff/news/news/list/2024/08/08/creating-a-flexible-contemporary-curriculum-for-adelaide-university.

- Heller, H 2016, The Capitalist University: The Transformations of Higher Education in the United States since 1945, Pluto Press, London.

- New Economic Thinking 2016, Wendy Brown on Education., YouTube, 7 June, viewed 10 April 2024, https://youtu.be/uFRGHXn0mRc?si=B_U_-oeL02GbaxKz.

- Psacharopoulos, G & Patrinos, HA 2018, ‘Returns to investment in education: A decennial review of the global literature’, Education Economics, vol. 26, no. 5/6, pp. 445–458.

- The University of Adelaide n.d., Global Academic Excellence 50% International Scholarship, The University of Adelaide, viewed 14 August 2025, https://international.adelaide.edu.au/admissions/scholarships/global-academic-excellence-scholarship.

- The University of Adelaide n.d., Global Citizens International Scholarship, The University of Adelaide, viewed 14 August 2025, https://international.adelaide.edu.au/admissions/scholarships/global-citizens-scholarships.

- UNESCO European Centre for Higher Education 1992, ‘Academic freedom and university autonomy: proceedings’, in International Conference on Academic Freedom and University Autonomy, Sinaia, Romania, 1992, CEPES, UNESCO European Centre for Higher Education, CRE, NRCR, Romanian National Commission for UNESCO, Bucharest, Romania.

Leave a comment