The views expressed in this article are solely my own and do not represent the official position of YEI, a nonpartisan think tank that provides a platform for its researchers to share independent perspectives.

To paraphrase Justice Robert H. Jackson’s famous opening address at Nuremberg, international law is an institution dedicated to the prevention and punishment of serious crimes that threaten the security of humankind[1]. Yet, the history of international criminal justice suggests that retribution is neither uniform nor impartial. When a one single high-profile individual is assassinated, international outrage is often swift and decisive. However, when thousands die in genocides or war crimes, justice can be delayed, obstructed, or entirely absent.

This disparity raises a fundamental question: does the killing of one provoke greater retribution than the killing of thousands? Examining the development of international criminal law, the limitations of institutions like the International Criminal Court (ICC), and notable cases of prosecution and indemnity, this article will explore whether justice is blind or whether its scales are tipped by politics.

Historical Foundations of International Criminal Law

The modern framework of international criminal justice was forged after the horrors of World War II. The Nuremberg and Tokyo Tribunals prosecuted leading figures of the Axis powers for crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. These trials set the precedent for holding individuals accountable for mass atrocities, rejecting the notion that state sovereignty shields perpetrators from prosecution. However, justice was not applied equally. The trials criticised for the evident ‘victor’s justice’, as only Axis leaders faced retribution while Allied war crimes were left unexamined. This selective approach persisted even after decades, shaping the uneven enforcement of international law.

Despite its limitations, the tribunals undeniably laid the foundations for prosecuting mass atrocities and without these trials, the principle that state actors can be held accountable for crimes against humanity might not have emerged. Efforts to establish a permanent international criminal court gained momentum in the late 20th century. The Rome Statute, adopted in 1998[2], created the ICC, marking a significant step toward global accountability. Unlike the ad hoc tribunals (temporary, spontaneously formed courts that are established to handle specific cases) for Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia, the ICC was designed as a permanent body to prosecute individuals for genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression. The creation of these tribunals suggests a continued commitment to punishing mass crimes, yet the court’s authority remains limited, raising critical questions about its effectiveness in delivering justice.

The ICC: Structure, Power, and Limitations

Based in The Hague, the ICC operates as a court of last resort, stepping in only when national jurisdictions are unwilling or unable to prosecute serious crimes. It can initiate cases through referrals by member states, the United Nations Security Council, or the ICC Prosecutor’s own initiative (proprio motu)[3]. However, its power is constrained by political realities.

Even when the ICC does issue arrest warrants, enforcement is often ineffective. Omar al-Bashir, wanted for genocide in Sudan, travelled freely to ICC member states without arrest for years[4]. This lack of enforcement starkly contrasts the swift legal debates and retaliatory actions following targeted killings, such as the U.S drone strike on Qasem Soleimani[5]. The inability of the ICC to act on large-scale atrocities, while individual assassinations provoke immediate international responses, reinforces that retribution is dictated by politics rather than the gravity of the crime.

Membership and Sovereignty Concerns

As of January 2025, 125 countries are parties to the Rome Statute. However, major global powers – including the United States, China, Russia, India, and Israel[6] – have refused to join, citing their concerns regarding state sovereignty and potential political bias. The absence of these key nations weakens the ICC’s ability to enforce its rulings, as non-members are not bound by its jurisdiction.

Selective Justice and Political Influence

The ICC has faced accusations of disproportionately targeting African nations, leading to criticism from the African Union and threats of mass withdrawal. The court’s failure to prosecute crimes committed by powerful states has further fuelled scepticism. For instance, while the ICC has pursued cases against Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir, it has been largely silenced to investigate alleged war crimes committed by U.S. forces in Afghanistan, (after the U.S. revoked the visa of the ICC’s Chief Prosecutor[7]) or Israeli actions in Palestine.

This disparity highlights a fundamental issue: justice is often pursued where it is politically convenient. When a single assassination – such as the targeted killing of Iranian General Qasem Soleimani in 2020 – occurs, international legal debates erupt over its justification under self-defence doctrines. However, when mass killings unfold in conflicts like the ongoing Syrian Civil War, accountability remains indistinct. The ICC’s reliance on state cooperation and its inability to enforce arrest warrants without international support severely limits its effectiveness to deliver justice.

The Weight of Retribution: One Death vs. Mass Atrocities

High-Profile Assassination and Global Response

The killing of a prominent political or military figure often sparks immediate global reactions. The U.S. targeted drone strike on Soleimani provoked intense legal and political scrutiny because it involved direct state action and a clear perpetrator.

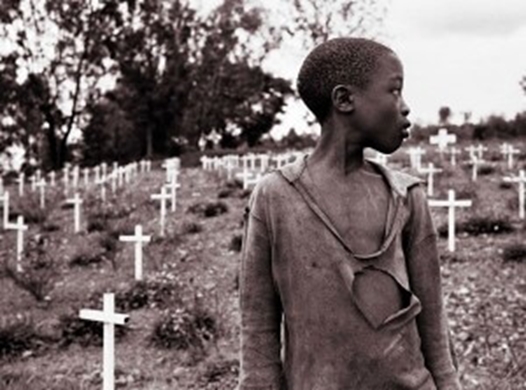

Delayed and Denied Justice

In contrast, mass atrocities often see delayed justice – if any at all. The Rwandan Genocide in 1994 resulted in over 1,100,000 deaths[8], yet major international intervention occurred shamefully late after the fact. More recently, the Rohingya refugee crisis in Myanmar[9] and the Uyghur persecution in China have faced international condemnation, but legal action remains minimal yet again due to geopolitical complexities.

Some may argue that the reason these mass killings do not receive immediate legal action is not due to a lack of retribution, but rather a complexity of prosecuting them. A single assassination has a clear perpetrator and legal framework, while war crimes often involve multiple actors, causing legal responses to be slower – but not necessarily weaker in the long run. However, this still does not explain why states actively obstruct justice. The failure to intervene in Rwanda despite clear intelligence reports, and the ICC’s hesitance to investigate U.S. war crimes suggest that delays are not due to legal difficulties but because of political considerations.

In contrast, when a single high-profile individual is assassinated – such as Soleimani – international outcry is immediate, and diplomatic consequences often follow. The disparity in response suggests that retribution is determined not by scale, but strategic interests.

This contrast reveals a troubling reality: while a single politically charged killing can provoke immediate legal and diplomatic consequences, systemic mass killings often face bureaucratic inactivity and political obstructions to justice.

Legal and Political Challenges in Prosecuting War Crimes

Arrest Warrants and Enforcement Challenges

One of the ICC’s key tools is the issuance of arrest warrants. However, enforcing them is another matter. When the ICC issued a warrant for Russian President Vladimir Putin over alleged war crimes in Ukraine, many states were reluctant to act, fearing diplomatic repercussions. The ICC’s reliance on state cooperation undermines its credibility. When politically influential figures are accused, states often shield them, making prosecution nearly impossible.

Double Standards

International law also suffers from double standards. The United States, for instance, has condemned torture globally but has not prosecuted its own officials for the use of torture during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. Similarly, while the U.S. advocates for the ICC to investigate war crimes committed by its adversaries, it has actively opposed ICC jurisdiction over its own actions. This selective adherence to international law diminishes its legitimacy and raises doubts about whether justice is truly impartial.

The Illusion of Equal Justice

The notion that international justice weighs all crimes equally is more aspirational than real. The killing of a single politically significant figure often generates swift retributive responses due to its immediate diplomatic consequences, while mass atrocities often face delays, political obstructions, and selective enforcement of international law.

The ICC, despite its foundational mission to prosecute the gravest crimes, remains constrained by state power and politics, with its successes overshadowed by its inability to hold the most powerful actors accountable. While international law aspires to deliver justice for all, its practice reveals a world where retribution is not measured by the number of lives lost, but by the geopolitical influence of those involved. Thus, the killing of thousands does not necessarily provoke stronger retribution than one politically significant individual. Instead, retribution is dictated by political and strategic interests rather than moral or legal principles. Justice is not blind, and the scales of retribution do not balance the lives lost, but rather the power of those who shape its enforcement.

Bibliography:

[1] William A. Schabas, An Introduction to the International Criminal Court, The International Criminal Court, p. 153

[2] F. Benedetti, K. Bonneau and J. L. Washburn, Negotiating the International Criminal Court, The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 2014, p.39

[3] Proprio Motu Investigation: International Criminal Court (ICC), Chantal Meloni, A. Introduction

[4] David Scheffer, All the Missing Souls: A Personal History of the War Crimes Tribunals, Princeton University Press

[5] Statement from the President Regarding Veto of S.J. Res. 68 (May 6, 2020)

[6] https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/role-icc, Summary

[7] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-47822839

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International response_to_the _Rwandan genocide, Introduction

[9] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-50931565, Myanmar, Rohingya: UN condemns human rights abuses

Leave a comment